-

On The Steel Breeze

- by Alastair Reynolds

- HC, Victor Gollancz, © 2013, 483 pp, ISBN 978-0-575-09045-3

On The Steel Breeze is the sequel to last year’s Blue Remembered Earth, although you strictly speaking don’t need to read Blue to follow Breeze. It takes place starting in the mid-2300s, so about 200 years after its predecessor. Thanks to life-extension technologies, a few characters from Blue are still around, but the book centers on Chiku Akinya, daughter of Sunday Akinya, one of the two principals of the first book.

Chiku has had herself cloned into three identical persons, memories evened out among them, and who then followed three different paths: Chiku Red flew after their grandmother Eunice’s ship, which had left the solar system at high speed at the end of the first book carrying Eunice on it. Chiku Green travelled aboard the Zanzibar, one of a fleet of starships (hollowed-out asteroids moving at more than 10% of light speed) heading to Crucible, a planet about 25 light years away which has what looked like evidence of alien intelligence on it, in the form of a strange object on its surface called Mandala. And Chiku Yellow stayed on Earth.

Most of the action takes place on Zanzibar, where Chiku Green has risen to a position on the council, but where the fleet is endangered by political turmoil and a more physical possibility that they won’t be able to stop before they fly past Crucible. She contacts Chiku Yellow on Earth who unearths some of the secrets that her sister has suspected, but at significant cost: Something threatens not just the fleet, but possibly every in the solar system as well, and there are surprises waiting at Crucible assuming humans manage to arrive there.

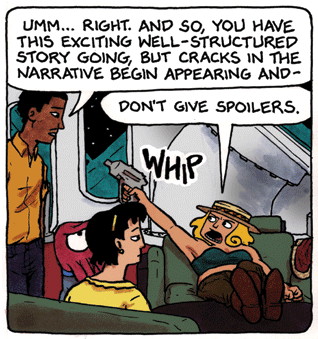

On The Steel Breeze, like its predecessors, is focused more on grand world-building than on clever plotting. The story is more sophisticated than Blue, the first book having disappointed me a bit in its fairly simply “quest” story. Breeze has more nuance in characters – mainly in the fleet – pursuing different agendas that are largely incompatible. Chiku Green makes some large personal sacrifices for what she feels is the good of her ship and her family. The characterizations are not Reynolds’ strong suit, and Chiku seems a bit too calculating in making her decisions. On the other hand Reynolds’ hand at politics is more deft than before.

The pieces of the story involving Chiku Yellow on Earth are the most exciting parts of the book, with a tense adventure on Venus followed by a hair-raising return to Earth. Her character arc is stronger, too, although as her tale fades into the background the closure her story achieves feels a little thin. The storytelling gimmick of telling the tale through the eyes of the two aspects of Chiku is clever in the first half, but doesn’t perhaps serve the characters the best in the second.

Of course there’s the alien presence at Crucible, which is not really the focus of the novel but plays some role at the end. It seems likely that it will be the focus of the third book.

Taken together, the two books feel like a modern take on Heinlein and Clarke styles of the future of humanity, expanding the world-building considerably. They’re very well-crafted works, but they do require some dedication as their pacing seems calculated to emphasize the world-building, and thus they’re not likely to be for everyone. I don’t count them among Reynolds’ best work, but I’m enjoying them so far. I’m hopeful that the next novel will bring a larger leap in technology and ideas content.